Consider: The Shipping Container

This past week the world learned how vulnerable global ocean shipping infrastructure can be to unplanned disruptions. When the Ever Given, carrying 18,300 containers, got stuck in the Suez canal for 5 days, it blocked a critical shipping channel and caused a reported backlog of +350 ships awaiting its clearance. The internet was quickly awash in hot-fresh memes and the Twitter vibe was a weird mix of absurdity, empathy and ridicule of the attempts to resolve it. Thankfully on Monday, the ship was freed, assisted by a combination of front-end loaders, dredgers, tugboats and high tide. Following along this week got me thinking about the origins of the shipping container. I was surprised to learn of their relatively short history, open source design, and outsized impact on the global economy.

Design

For centuries, ships have been used to transport goods as a faster alternative to overland and as a way to reach new oversea markets. Think back and imagine the dockside chaos of loading and unloading hundreds of sacks and barrels to and from ships. Misdirected and “lost” cargo were pain points, nevermind the immense amount of labour and time required. Early shipping crates / containers were an antidote to these issues and according to the World Shipping Council, “boxes similar to modern containers had been used for combined rail- and horse-drawn transport in England as early as 1792. The US government used small standard-sized containers during the Second World War, which proved a means of quickly and efficiently unloading and distributing supplies.”

American freight entrepreneur Malcom McLean came up with the idea of an “intermodal” container that could be transported by truck, rail or sea, but more importantly streamlined the cargo loading process. As this great New York Times video explains, he believed the “key wasn’t faster boats but to build faster docks”. In 1955, he commissioned the design of a standardized container and modified an oil tanker, on which he loaded up the top deck with containers. On April 26, 1956 the Ideal X sailed from Newark to Houston with 58 containers.

Innovation

After their initial development and adoption, shipping containers still lacked one critical element: standardization. As Discover Containers explains,

“… uniformity was needed so containers could be stacked efficiently. Additionally, trains, trucks, and other transport equipment required a standard-sized container so each method of transport could be built to a single size...During the Vietnam War, the US government was looking for a way to ship goods more efficiently and was pushing for standardization. McLean’s SeaLand Industries was still using 35-foot containers, while industry rival Matson’s were using 24-foot containers. McLean agreed to release his patent of the revolutionary shipping container corner posts (vital to its strength and stacking) and several standards were agreed upon.”

In 1968 ISO standards were set which defined the now ubiquitous 20 foot and 40 foot shipping containers used worldwide. McLean was willing to open source his design in exchange for the benefits of network effects.

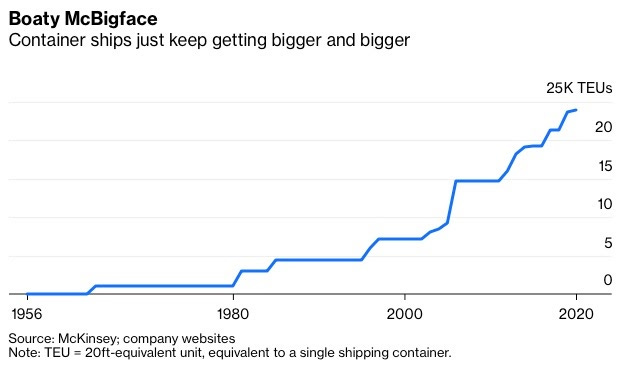

In the past 50 years, innovation has continued within the shipping container ecosystem. Most visibly, the size/capacity of the ships (like the unfortunate Ever Given) has ballooned to handle upwards of 20,000 TEU (Twenty foot container Equivalent Units) containers, with Bloomberg reporting that there are ships “being assembled in Chinese and South Korean shipyards (that) are mostly around the 24,000 TEU capacity“, a further 20% increase! The graph below shows a +4x increase in capacity in just the past 20 years.

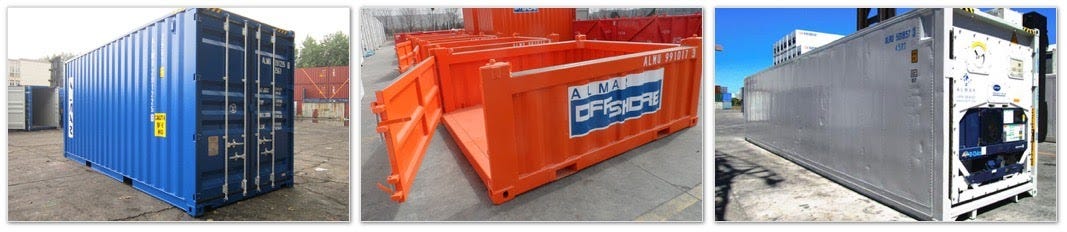

In addition, the types of shipping containers have increased, all while staying standard in the dimensions/design of the corners. You now have dry freight, “reefer” or refrigeration containers, open-top and tank containers.

Sustainability

I often find the Sustainability section of Considered to be the toughest to craft. Perhaps because it means different things to different people, along with its now common (and loose) use and the fact that there are no simple answers. The modern shipping container is a great example of the cognitive dissonance of sustainability. How do we weigh the benefits of efficiency versus the challenges of widespread use and globalization?

One one side, containers designed for shipping and stacking are generally made out of steel and can be recycled at the end of their useful life (or repurposed as immobile storage or structures). They have helped drive down the cost of shipping world wide by reducing loading times, shrinkage and taking advantage of economies of scale. Because of all these benefits, this has resulted in a massive shift in the global economy with container ships now moving “95% of all manufactured goods in the world”.

One the other side, an article from Vice puts it plainly: “They perfectly convey the direction in which modern capitalism continues to develop: a mass-produced, transitory, transnational, automated, human-erasing beast.” Further, an article from The Atlantic shares the perspective of geographer David Harvey who has argued that,

“these objects play a critical role in the changing nature of our cities, our politics, our labor, as well as our shopping habits. Without the container, cities like the Port of London would not have changed in such a dramatic manner. Harvey calls this process deindustrialization —the removal of a region’s heavy industry. Likewise, without the container and deindustrialization, the availability of cheap imports from China and other emerging economies would not have been possible.”

Finally, the movement of shipping containers comes with its own environmental impact. Although more efficient than other modes of cargo transport, a 2019 study calculated, “Marine transportation is responsible for 2–3% of global greenhouse (GHG) emissions and is predicted to increase to 17% by 2050 if left unchecked”. Thankfully the industry is responding and has set targets to reduce emissions by 50% (compared to 2008) by 2050. Alternative fuels (hydrogen, solar) and ship designs (sails, foils) are all being Considered.

Value

New containers go for ~$3,000-$5,000, while used ones can be found for less than half the price. Even from when they were first introduced, shipping containers have been more economical than their alternatives. As a story from the Port Authority of New York highlights, “In 1956, the cost of loading a ship was $5.86 a ton compared to 16 cents, the cost to load a container onto a ship, which was a 39-fold savings.” Today it’s estimated that the cost of shipping a container full of 10,000 iPads from Asia to North America comes in at a shockingly small $0.05 per unit.

Thanks again for coming aboard this week! If you enjoyed this week’s Considered, hit that 🖤 button below, or better yet, share it with a friend.

Because the world needs more sax, enjoy this unconventional tugboat-alto duet: